Building Good Boats from the Bottom Up

An interview with Frank Mulder

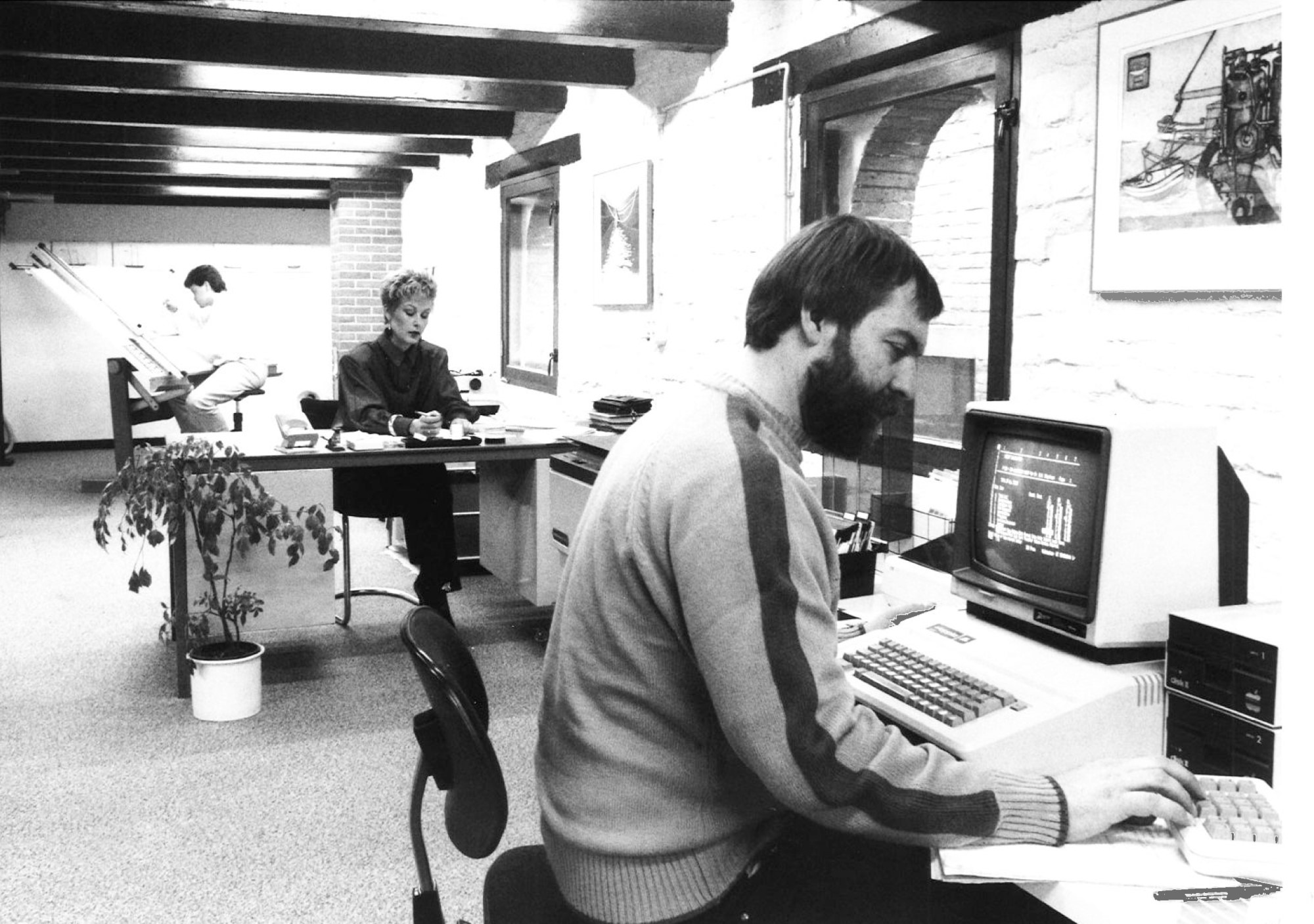

Frank Mulder’s professional background began with working in a shipyard – Amels – where his “office” was a niche in the wall of a construction shed and his first job out of university in 1974 was as Assistant Yard Manager scheduling production. Two years later he was offered a post as a naval architect by Damen and made head of its high-speed division for military and commercial craft. Three years after that, he made the brash decision at age 28 to quit the safety of a career at Damen and open his own studio. That type of “sink or swim” decision is characteristic of the senior Mulder.

Q: Looking back, did you ever feel typecast as a fast boat specialist?

FM: “It is fair to talk about me as a high-speed designer, our fast boats got us in the door and got us noticed. However, we have done many more moderate-speed boats.

Q: Many people think your first superyacht was Octopussy, but it wasn’t, was it?

FM: No, we had already done six yachts at Heesen when Octopussy began in 1989. My studio was doing navy and customs boats for Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong when Frans Heesen called in 1984 and asked for help on a small job. Then came an order for the Tropic C.

Tropic C was a custom, 36.9m aluminium tri-deck yacht with a fishing cockpit at the stern and a flying bridge. Five staterooms and four crew cabins accommodated 11 guests and 8 crew. Mulder’s first round-bilge semi-displacement yacht, her top speed was 20 knots. This was followed by 34m Wheels in 1987, Mulder’s first round bilge, semi-planning yacht.

Q: Octopussy began with a phone call from a sales executive at MTU about a client who had bought three high-horsepower engines and wanted the world’s fastest yacht built around them. How did you approach the design?

FM: I was in my office when John Staluppi called me. His first question was, “Can you design a yacht that goes 50 knots?” I was on the spot and I said, “Let me look into this and I will call back soon”. I calles him back after one hour and said: “Yes. I can” John arrived next morning in Amsterdam accompanied by his captain and the same question, could I design a yacht that would go faster than the King of Spain’s Fortuna? It was clear that he wanted a full yacht of 120 to 140 feet and not just a racing boat. He wanted a firm answer in two weeks.

Q: Has the advance in materials changed your design process?

FM: Not so much. Design should always be done and completed on paper before someone starts cutting metal or fibreglass. We started into composites with Moonraker launched in 1992 at Norship. We never felt that composites were a risk for yachts that would do over 30 knots, many passenger ferries do that. Carbon fibre is a different thing altogether. I see boats with carbon fibre superstructures, but it is so stiff, so much stiffer than glass reinforced composites, that it's best to do the whole boat out of it. But why? It is many times more expensive and what do you save for it? A couple less support pillars? For regattas, it’s important, but that’s not our market.

Q: Then came one of the most interesting contracts in superyachting.

FM: I told him I thought it could be done but I would need six weeks to design and test it. If the tests say it can be done, you have to build it. If it can’t be done, he would have to pay me $65,000 for the tank testing and my time.

The rest is history and Mulder’s Deep V forward sections transitioning hard, lifting chines and a planning aft section with three 3,500hp engines all driving KaMeWa water jets gave rise to what was known as the Jet Squadron, a pack of highspeed superyachts that defined a trend in the early 1990s. Mulder Design, under the leadership of Bas Mulder, is working on the third refit of this iconic yacht.

Q: Mulder works on commercial projects as well as small production boats and custom yachts – 1,000 vessels all totalled. Is there a signature Mulder hull?

FM: I get asked all the time, “What is the best hull design?” That is the biggest mistake you can make. We work on what design is best for the project as a whole. It doesn’t matter if it is a yacht where the balance is between luxury and mechanical space or on commercial vessels where it is the size of the hold vs. the engine room. You need to be flexible for the project, now they call it holistic design. You have to think about the yacht from all perspectives – the chef, the engineer, the owner, to the yard. Don’t design something where the yard had to hang a guy upside-down to weld it.

Q: Where have the biggest changes in naval architecture come from?

FM: Computers. In 1970, I bought a 1K programmable computer and used it for 10 years. We kept upgrading when new tools came out but Octopussy, for example, was drawn by hand. All the drafting was done in the yard by hand. I was the first to buy a MaxSurf in Holland in 1989, then we started designing in 3D. Moonraker’s superstructure was designed in Maxsurf in 1991. I printed out the pieces on polyester one-to-one scale and mailed them to the yard in Norway. I’ve spent 35 years behind a computer.